377x Filetype PDF File size 1.88 MB Source: www.math.uh.edu

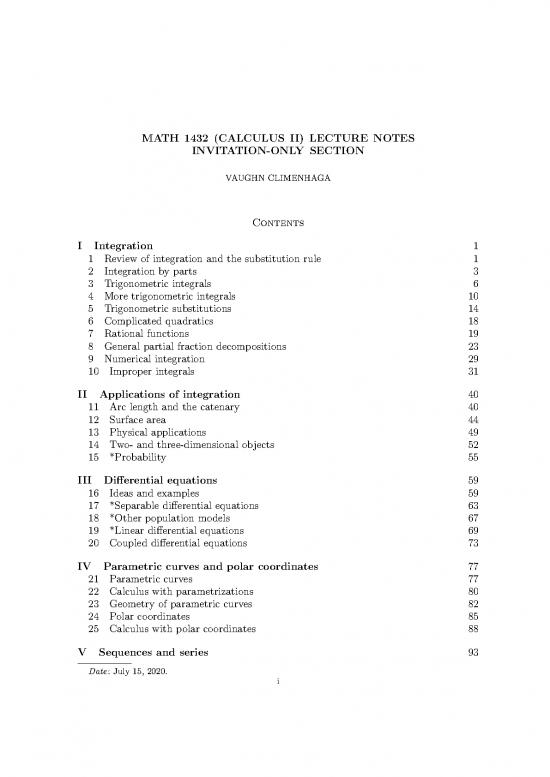

MATH 1432 (CALCULUS II) LECTURE NOTES

INVITATION-ONLY SECTION

VAUGHNCLIMENHAGA

Contents

I Integration 1

1 Review of integration and the substitution rule 1

2 Integration by parts 3

3 Trigonometric integrals 6

4 More trigonometric integrals 10

5 Trigonometric substitutions 14

6 Complicated quadratics 18

7 Rational functions 19

8 General partial fraction decompositions 23

9 Numerical integration 29

10 Improper integrals 31

II Applications of integration 40

11 Arc length and the catenary 40

12 Surface area 44

13 Physical applications 49

14 Two- and three-dimensional objects 52

15 *Probability 55

III Differential equations 59

16 Ideas and examples 59

17 *Separable differential equations 63

18 *Other population models 67

19 *Linear differential equations 69

20 Coupled differential equations 73

IV Parametric curves and polar coordinates 77

21 Parametric curves 77

22 Calculus with parametrizations 80

23 Geometry of parametric curves 82

24 Polar coordinates 85

25 Calculus with polar coordinates 88

V Sequences and series 93

Date: July 15, 2020.

i

ii VAUGHNCLIMENHAGA

26 Sequences 93

27 Summing an infinite series 98

28 The integral test 101

29 Comparison tests and alternating series 105

30 Absolute convergence, ratio and root tests 107

31 Power series 110

32 Calculus with power series 113

33 Taylor and Maclaurin series 117

VI Conic sections, planetary motion 126

34 Parabolas 126

35 Ellipses (and hyperbolas) 131

36 Kepler and Newton 136

1

Part I. Integration

Lecture 1 Review of integration and the substitution rule

Stewart §5.5, Spivak Ch. 19

1.1. Definite and indefinite integrals

Last semester, we motivated the introduction of integrals by considering the question

of how to determine areas. This led us to two definitions:

(1) the definite integral Rb f(x)dx is a number obtained as a limit of Riemann sums,

a

which depends on the interval [a,b] and can be interpreted as an area;

(2) the indefinite integral R f(x)dx is a function whose derivative is f(x).

The two are related by the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, which has two halves.

The first half says that definite integrals can be used to find indefinite integrals (an-

tiderivatives), since d Rx f(t)dt = f(x).

dx a

The second half goes in the opposite direction, and says that indefinite integrals can

be used to find definite integrals: if F(x) = R f(x)dx is an indefinite integral of f, so

that F′(x) = f(x) at every x, then Rbf(x)dx = F(b)−F(a).

a

Although the first half guarantees that every continuous function has an indefinite

integral, it does not give a general procedure for writing down an elementary formula

for R f(x)dx. Our emphasis for the next little while will be on this process, which is

essential if we are to use the second half of the FTC effectively.

By “elementary formula”, we mean a formula that can be written down in terms

of constants, polynomials, rational functions, exponentials, trigonometric functions,

and logarithms using addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. For exam-

ple, F(x) = tan−1(x) is an elementary formula, but F(x) = Rx 1 2 dt is not elementary

0 1+t

because it involves an integral, even though it represents the same function.

Given an integral R f(x)dx, then, our goal will be to find an elementary formula for

it. Bear the following warning in mind, though: not every integral admits an elemen-

1 R 2

tary formula. For example, it is possible to show that sin(x )dx does not have an

elementary formula, and in fact there is a sense in which most indefinite integrals do

not have elementary formulas. Nevertheless, a great many of them do, including some

of the most important ones, and so we will turn our attention now to finding them.

1.2. Substitution rule

The first method of integration is by direct inspection: we have a list of functions

F(x) whose derivatives f(x) = F′(x) are known, and if f happens to appear on the

corresponding list of derivatives, then we can simply read off the indefinite integral

R f(x)dx = F(x)+C.

1

The proof involves tools that go beyond the scope of this course, and we will not discuss it.

2

The second method, which we encountered briefly last semester, is the substitution

rule. This is a consequence of the chain rule for differentiation, which says that if F,g are

′ ′ ′

differentiable functions, then F ◦g is differentiable and has (F ◦g) (x) = F (g(x))g (x).

In particular, if F′(x) = f(x) so that F gives the indefinite integral of f, then we have

(F ◦g)′ = (f ◦g)·(g′); this can be written in the form

Z f(g(x))g′(x)dx = F(g(x)).

It is usually easier to remember and apply this rule if we introduce a new variable

u=g(x), and observe that d F(u) = f(u), so that the above formula becomes

du

(1.1) Z f(g(x))g′(x)dx = Z f(u)du.

It is common to rewrite the formula g′(x) = du as du = g′(x)dx, in which case (1.1)

dx

appears to become almost trivial:

Z f(g(x))g′(x)dx = Z f(u)du.

|{z} | {z }

u du

We emphasize, though, that the formula du = g′(x)dx is purely a bookkeeping device

rather than a valid part of a proof, because we have not yet given du and dx any

independent meaning of their own. We will continue to use it because it simplifies the

appearance of various computation, but please remember the logical order of things:

(1.1) justifies this formula, rather than the other way round.

R √ 2 2

Example1.1. Wecancompute x 1+x dxbyputtingu=1+x sothatdu=2xdx,

and we obtain

Z √ 2 Z √ 2 Z 1 1/2 1 2 3/2 1 2 3/2

x 1+x dx= 1+x ·xdx= u du = · u +C= (1+x) +C.

| {z } |{z} 2 2 3 3

√ 1du

u 2

Example 1.2. To find R tanxdx, we can write tanx = sinx and notice that the deriva-

cosx

tive of cosx appears in the numerator (up to a negative sign), so putting u = cosx gives

du = −sinxdx and

Z tanxdx=Z sinx dx=Z −du =−ln|u|+C =−ln|cosx|+C =ln|1/cosx|+C

cosx u

=ln|secx|+C.

There is no universal procedure telling us how to make the change of variables u =

g(x), but these examples illustrate some guidelines that are helpful to keep in mind: it

is reasonable to try setting u as the input of some function in the integrand (the square

root function in Example 1.1), or as an expression whose derivative also appears in the

integrand (the cosine function in Example 1.2). Sometimes it even works to let u be

the entire integrand: for example, in R √2x+1dx we can take u = √2x+1 so that

u2 = 2x+1 and 2udu = 2dx, and we get

Z √ Z 1 3 1 3/2

2x+1 dx = u·udu= u +C= (2x+1) +C.

| {z } |{z} 3 3

u udu

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.